Jan. 06, 2025 | By Paul Lagasse, Medical Research and Development Command

FORT DETRICK, Md. – As geopolitical competition in the Arctic region continues to accelerate, senior leaders need to be confident that the Warfighters under their command will be able to operate at peak effectiveness for long periods in extreme cold. That’s why experts in nutrition, physical performance, and extreme environments from the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine are teaming up to revise the Army’s guidance on protecting the physical and psychological health of military personnel operating in below-zero environments.

In the nearly 20 years since the last edition of the Army’s technical bulletin on the prevention and management of cold-weather injuries, called TB MED 508, research conducted at USARIEM has significantly improved our understanding of how humans respond and adapt to cold, how to effectively prevent and treat cold injuries, and how to inhibit performance degradation. That knowledge will be reflected in the new edition of TB MED 508.

“One of the things we teach Warfighters is that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution in cold-weather operations,” says Dr. John Castellani, a supervisory research physiologist at USARIEM and the organizer of USARIEM’s Cold Weather Research and Development/Arctic Medicine Cross-Functional Team. “Some people might need to wear an extra layer, while other people might not. Everybody's different. That being said, hands and feet are the most susceptible and we really need to try to protect them as much as possible.”

For example, the ability of a person to generate heat and sustain it are affected by their muscle mass, fitness level, age, and fatigue. With that in mind, USARIEM has developed the Cold Weather Ensemble Decision Aid, a computer database that allows individuals to select the headwear, gloves, boots, and upper- and lower-body gear that best suits their physical characteristics and their operating environment. Future updates to the decision aid will include cold-weather ensembles from the U.S. Air Force and other NATO countries, as well as enable users to calculate the effects of wet clothing on heat loss.

Castellani recently discussed these and other interesting developments in Arctic force health protection at the annual Anchorage Security and Defense Conference, a two-day symposium co-hosted by the Ted Stevens Center for Arctic Security Studies and the Department of Homeland Security’s Arctic Domain Awareness Center. For the first time, over 350 defense and security professionals from the United States, Canada, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and other NATO countries gathered to discuss how to address the security challenges currently facing the Arctic region, including the role of cold-weather military medicine.

One of the most important developments in the treatment of cold-weather injuries, according to Castellani, is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s recent approval of the drug iloprost for treating severe frostbite, the first approval of its kind by the FDA. Originally developed to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension, iloprost works by dilating blood vessels to improve blood flow. Research has shown that this technique is effective in treating deep frostbite that penetrates beneath the skin to affect muscle, tendon, and bone.

“The efficacy of iloprost is amazing,” says Castellani. “If people can get it intravenously within 72 hours of an injury, the likelihood of amputation is severely decreased.”

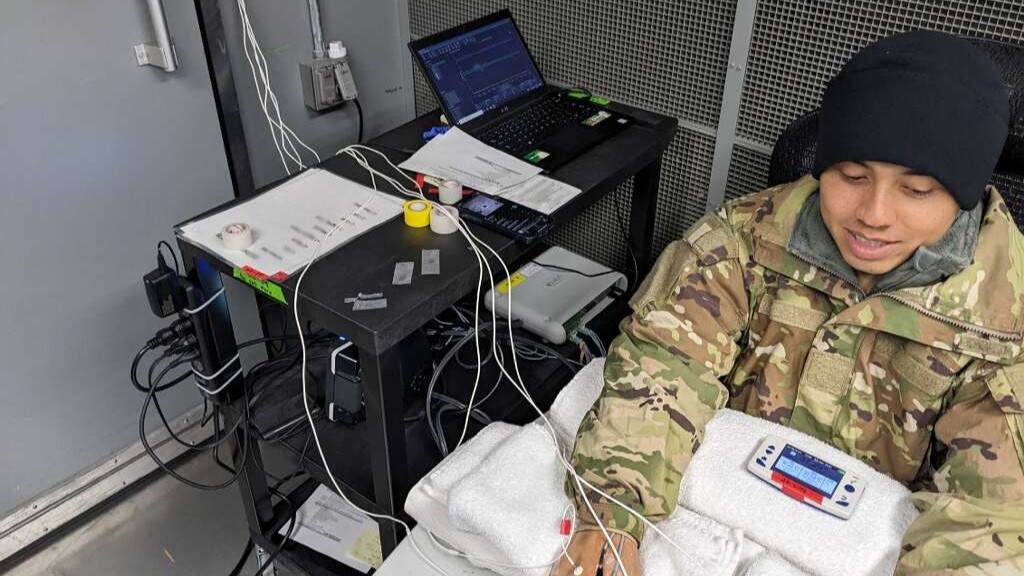

USARIEM’s Cold Weather Research and Development/Arctic Medicine Cross-Functional Team brings together researchers from across USARIEM’s Military Nutrition, Military Performance, and Thermal & Mountain Rescue research divisions to address science and technology gaps in cold-weather medicine and performance. Their goal is to enhance Warfighter performance and medical treatment in extreme environments. The team focuses on four broad thematic areas: developing guidance and standards, sustaining manual dexterity and peripheral blood flow, improving physical and cognitive performance, and ensuring adequate nutrition.

Research conducted by members of the cross-functional team has explored topics as wide-ranging as how energy deficits impact the body’s ability to maintain muscle mass, how blood flow to the hands and fingers can be increased to improve manual dexterity, and how to map the timeline of frostbite injury recovery to help accelerate return to duty. Eventually, Castellani hopes the Army Medical Capability Development Integration Directorate will use the findings from these and other studies to develop new requirements for human performance and preventive medicine in extreme environments.

“It costs so much less to prevent an injury than it does to treat it,” says Castellani. “Ultimately, the goal is to provide tools to people so that they can make informed decisions to prevent injury in the first place, and to allow them to thrive rather than just survive.”